Six Selections on Self-Defense

An extended, scope-expanded Defense Against the Dark Arts class

Introduction

Self-defense,1 as described here, refers to holding onto your dreams and cares.2 It refers to not losing certain parts of you that make you, you.

It refers to not letting your desires be superseded by other people’s and other institutions’ desires.3 It refers to a preservation of the self, some sort of mental and emotional resistance, against powerful memes. Think effective altruism, rationality,4 startup culture, various religions and political groups—but there are more examples.5 Self-defense is a nebulous concept; it falls into the bucket of “when you see it, you know it” ideas.

I have written below six selections on self-defense. Some are solely sermons; some are moreso memoirs. Between none and all of them may be relevant to any individual person. If you don’t think or feel a section applies to you, it might not, and in fact, following the exact opposite of what I write may be correct, for some people.6

Expand // Express

(Or: keep your identity broad.)

When I was younger—high school through the first half of college—I thought myself a “math and music person.”

Before midnight, I practiced piano masterpieces, soaking in and living for certain wonderful moments—those three B-flat octaves in Beethoven’s Les Adieux sonata; this ethereal, distant melody in Chopin’s Fantaisie in f. After midnight, I played choose-your-own-adventure games in GeoGebra, sprinkling a point here and a circle there, and thinking this line should be dashed and blue and that quadrilateral’s cyclic!.

I loved math and music. The freedom, the agency, the knowledge that I could create—create!—sounds and structures I loved beyond words. Sandboxes, pocket dimensions, infinite playgrounds. Time I spent tinkering didn’t feel like time.

“Athlete” was for classmates speeding through sub-five-minute miles; I slowed down each year of cross-country. “Humanities person” was for classmates brave enough to take AP European History and Shakespeare. Those were things I was not. So “math and music person” made even more sense.

Internally, I knew myself as a math and music person, and externally—when writing personal essays, when interviewing, when introducing myself to my college classmates—I described myself as a math and music person.

So falling out of love with math sucked. As a freshman, I was accepted to attend a summer math REU—research experience for undergraduates—but it went virtual due to the pandemic. Cooped up in my grandma’s old room, I studied alone for months, deciphering (or failing to decipher) “d_alpha matrices” and “Weyr canonical forms” with little support. I had a mentor, whom I met with on Zoom, but no companionship.

Companionship had drawn me to math. My best friends were math people. I balked at a conception of math without community. I quit.

I scrambled to replace this part of my identity. Since I was no longer a “math and music person,” was I just a “music person”? If I’d lost my love for piano, or if even worse, it was taken away from me (through injury, for example), what would I be then?

I’d constrained my identity, staked it upon two large-but-not-all-encompassing facets of myself, and when I lost one I drifted for years, uncertain and afraid, unable to commit to taking another direction seriously. I flirted with the idea of going into education, a catch-all a “math person” could audible into. I even considered about music school—the “only option left.” Calling myself a “math and music person” had led me to spurn other subjects, other modalities of learning; had led others to perceive me this way, which made it more difficult to redefine myself; had led me to believe that math and music were the only things I could do.

That was a mistake.

That was a mistake—the kind that starts out small, and accumulates more and more weight until it crushes you.

It took me years, but today, I’m more careful with and more free with my identity. I’m a pianist. I love the music of Holden Mui. I have a math degree, and I used to like math a lot but haven’t done it in a while. I really love writing, but don’t do enough of it. I both enjoy working out and enjoy the aesthetic of working out. I run long distances. I’m a great editor, at least for specific types of writing. I work in healthcare software. I spend a lot of time in weird communities comprised of alumni of camps I worked at, and I help some of those alumni apply to college. I’m (almost completely) vegetarian and don’t own a car. I like watching Magic: the Gathering drafts and tennis matches.

I can’t say all of that when I meet someone new, but it’s in my head, and that’s half the battle.

Your identity doesn’t have to include only things you’re good at. Your identity can include things you suck at. Your identity can include random fascinations. Your identity doesn’t even have to be about “things.” Your identity can be as broad as you want it to be. And beyond having a broad identity, acknowledging and reiterating the broadness of your identity is self-defense.

I think this is a big part of why some grad students feel depressed and burnt out. Imagine making your whole life about one thing and not being able to succeed at that one thing, by conventional metrics of success, or according to your mentors and advisors. And if for some time you fall out of love with that one thing, what is there left to do?

These days my cares and interests and loves are broad enough, stable enough that the relinquishing of any one cannot induce a crisis.

Verbalize // Vibe

(Or: you are allowed to sidestep arguments.)

Say I’m trying to convince you of my stance on Proposition A. (I’m in favor.) I’ve compiled experts’ video testimony. I’ve written documents with rigorous arguments and conclusions. I’ve assembled and refuted common counterarguments.

You’ve done something similar, and we’re looking at the results. We agree the depth and breadth of my knowledge of Proposition A, and everything surrounding proposition A, far exceeds yours.

Should you now be in favor of Proposition A?

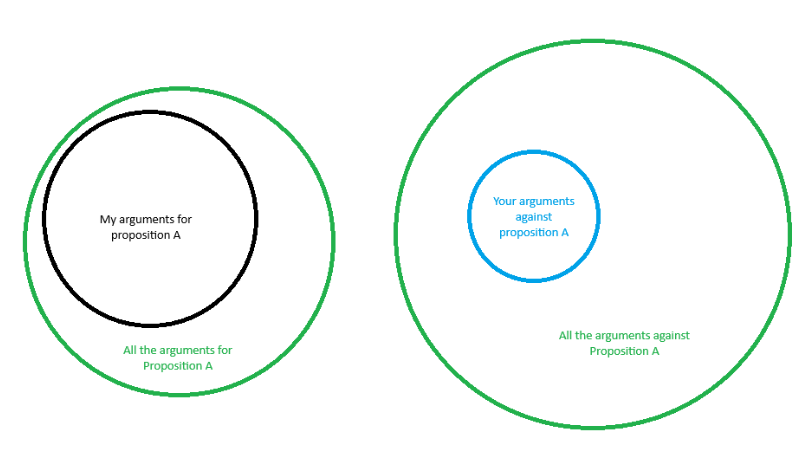

Well, maybe. Here’s a (naive and imprecise) visual—circle size represents the strength of the arguments.

Here’s how this could have occurred:

I might be a better researcher than you, even if my beliefs are less defensible;

You might need more time than I to compile information, and with more time the (blue) circle encompassing your arguments would’ve outgrown the (black) circle encompassing my arguments;

The information readily available about Proposition A supports it, but less rigorous evidence (gossip, anecdote, vibes-based pattern-matching) exists against Proposition A.

Translating these bullet points into real-world scenarios:

People better at arguing than you should not be able to convince you of things just because they are better at arguing than you are. If someone puts together a convincing argument of why you should support their political cause, or join their organization, or believe in their conception of impact—and if you can’t refute their points easily—that does not mean that you must fall in line.

Once you’ve been presented a compelling argument to join the Democratic Socialists of America, or work at a friend’s new education nonprofit (she swears it’s going to fix the school system), or make your life’s mission maximizing malaria net donations, you don’t have to make a decision instantly. You can sit there with the new thought(s) you’ve been given. You can let them stew. Move at a pace at which you feel comfortable.

Finally, even if you’ve decided what someone is saying is logically sound, you don’t have to go along with it. Maybe it felt like the people at your local church got a little too physically close to you. Perhaps you heard through the grapevine that Berenice never follows through with any of her projects. Or you somehow are certain that your mental state would crumble if you spent your life thinking only about impact, despite not technically having evidence of such.

These problems are exacerbated when the person arguing with you has some sort of power over you—be they a parent, or mentor, or older, “wiser” friend. You do not have to immediately take to the first strongly-defended opinion you hear about something. Your previous beliefs—or even lack thereof—sometimes deserve better.

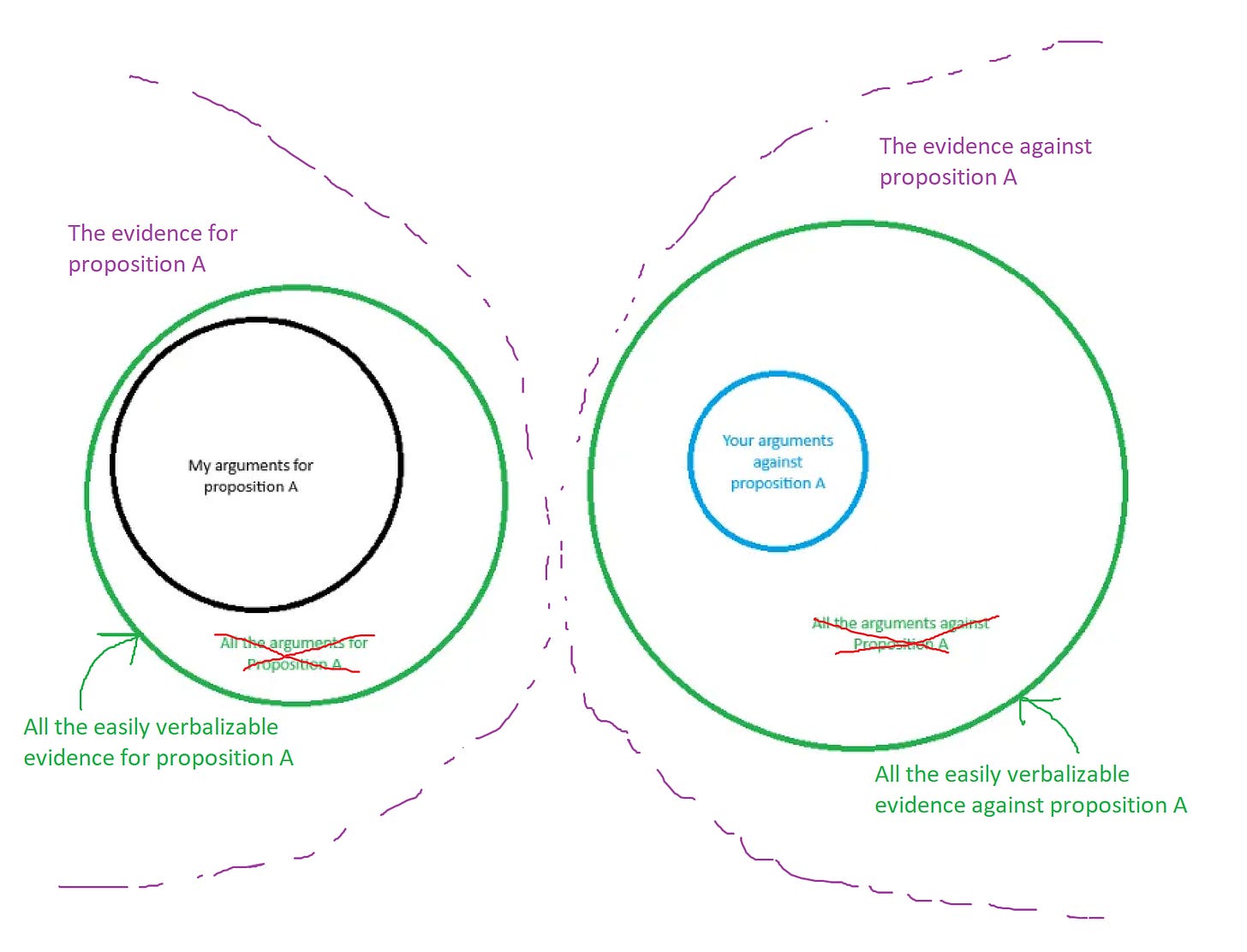

One more important extension: arguments are generally expressed in words. In fact, the aforementioned arguments are but one form of evidence—a much more general concept. Words are necessarily a reduction of reality—reality is too high-dimensional to capture fully.

So here’s another diagram.

For almost anything for which there can be evidence, there must be evidence that cannot be expressed in words.

Some people are very, very, very good at puppeteering words, at twisting reality until all you see is what they want you to see. There is something missing. If all you have to defend against an argument is a vibe, not all evidence can be verbalized.

If you wait and let their argument sit in your mind, you might be able to put words to what you’re feeling, but until then, you don’t have to argue with them. You don’t have to argue that they’re wrong or even rigorously convince yourself that they’re wrong.

You are allowed to listen to your feelings and emotions. You are allowed to sidestep arguments you don’t feel like engaging with.

Expose // Empower

(Or: who gets power over you?)

When you show someone some slice of your soul, you expose yourself and empower them.

At my first ESPR, I spoke to David about how difficult it was to find friends, about how I’d wasted away my first semester of college playing Secret Hitler, about how I hadn’t managed to make deeper connections.7 He told me I could change the social equilibria I fell into, that I could act outside the paradigm of “Game Night.”

When I returned to school the following year, I began asking people to go on long walks with me. They were lovely walks. I got to explore New Haven more thoroughly and became much better friends with a handful of people. (Later, some of them would even ask me to go on walks too!)

Had I been somewhat younger, with less self-defense, and had David been a very different person, he might have convinced me my classmates weren’t worth it. That to be happy, I had to return to environments like ESPR. He might have convinced me, in the way that so many young, ambitious people are convinced, that my classmates were not interesting people. I’d have been far more socially isolated than before—for years, or even for an entire lifetime. When you speak with parents, mentors, or close friends—people with power over you—you (often unknowingly) accept that these people can influence the way you think, feel, and act for a long time.

Some people will have power over you. So how do we choose who to give power to? And how much power?

I’ve thought about these questions with respect to my mom, who is uniquely good at making me feel bad. When she says you’re stupid and arrogant because you’re not studying for the GRE or this isn’t worthwhile because you’re not going to make any money, it burrows itself deep in my soul. As I entered high school, I told her less and less, and became less vulnerable to her omnipresent opinions on what I was doing and what I should be doing instead.

I’ve thought about these questions with respect to programs like SPARC or FABRIC. At these camps, when you play Hot Seat8 on night zero, when you go on long walks and have vulnerable, introspective conversations with other students and staff, you give people you’ve just met a surprising amount of power over you—and that’s not normal! Not every friendship has to be close and personal; there is value without vulnerability. Hell, not everyone has to be a friend.

Most people don’t necessarily have your best interests in mind, even if they think they do. People—even (and especially!) parents—have their own agendas.

So here’s how I choose who to give power to: I find people who really listen to me, who are willing to try and see things the way I do, not just filter my words through their own lenses. I track strong environmental forces that may alter my perceptions of people—when everyone around you admires someone, it’s easy to default to the same. I remind myself that friends I’ve known for only a few days, no matter how kind and thoughtful they might seem, are still mostly strangers—strangers I love, but strangers nonetheless.

Sometimes though, we don’t have a choice. Regardless of openness, older people—especially successful, “wise” older people—tend to have some power over us. We lend them more trust; we take their ideas seriously.

And if you’re a young person trying to figure out how to live—the most difficult question of them all—you are liable to (older) people convincing you that you are a failure if you’re not running a startup by eighteen, or if you’re not earning six figures by twenty-five, or if you’re not gunning for Forbes Thirty under Thirty. If you are unsure about your own values, you are so, so liable to absorbing the first set of seemingly-logical-and-consistent values presented to you.

So how do you stop giving people power over you—if you want to?

Keep track of what you (think you) value, and write it down for yourself. Be aware of who in your life can make you feel strong emotions. Question yourself if near-strangers can compel you to irreversible action. Be skeptical of sages and gurus.

Have an internal life—a real one. Certain parts of the world reward openness, vulnerability, or at least a flavor of such, and that is dangerous. Revealing too much of yourself leaves you to the mercy of others’ reactions and judgments. In some sense, openness precludes authenticity. Do you want to be beholden to strangers?

(But you, when you pray, go into your inner room, close your door and pray to your Father who is in secret […])

There are people in my life whom I love very much, people that I am glad have power over me. Good friends; a few select mentors; my younger sibling; and even now, my parents, still. They are deserving of this power. I accept the lows with the highs, because they have proven themselves over and over again.

Most have not. Where you draw the line is up to you.

Online // Outside

(Or: touch grass!)

The easiest way to practice self-defense is to go outside.

If you spend too long staring into the void of Instagram reels or TikTok, you forget what the real world looks like. (It’s somehow less bright and yet far brighter, at the same time.) You might feel pressure along any number of axes—pressure to accumulate more money, or more stuff; pressure to look nicer, to look better. Avoid the manipulation. Go outside.

If you spend too long embroiled in Twitter arguments about shrimp welfare or housing or well, what really is free speech?, you’re letting algorithms and other people control your behavior—likely for the worse. You might be damaging your eyes and posture and conception of humanity. Avoid the manipulation. Go outside.

The outside world is really beautiful. Take a screen break; take a device break entirely, even. Leave the earbuds at home. You have a physical body that exists in a physical world.

Spend time with friends and family in person, or people who you’re certain genuinely care about you. See how the outside world is larger and more complicated than words or pictures or sounds from your screen. Notice the freedom in being a person extends far beyond scrolling, clicking, engaging, and blocking.

(This section is not suited for yapping. Go touch grass right now!)

Narrowed // Nuanced

(Or: embrace nuance and the broadness of reality.)

I am both skeptical of and scared of simple conclusions.

Less “I can’t do math,” and more “it’s been a long time since I tried to do math, but with enough effort I can get back to how good I used to be, and even get better than that.”

Less “I despise the rationalists,” and more “rationality has done really weird and harmful things to the brains of lots of people I do care about, and rationalists associate themselves with some of the worst ideas and people ever, but they’ve also identified some really important truths and some people I really like and admire call themselves rationalists.”

Less “most people aren’t interesting,” and more “if you find someone uninteresting, you might not be talking to them about the right things, or they might be wary of sharing more of themselves with you for some reason, or you or they might just be kind of tired, or even something else.”

Less “this person is unambitious,” and more “this person doesn’t seem to be ambitious about the things you associate with ambition—let’s say, impacting the world positively through science and technology, or rising through the ranks at a major company—but maybe their definition of success is different or maybe you’re just not seeing their vision.”

Less “my piano technique is broken,” and more “I lack experience with specific techniques—fast thirds and very dense counterpoint, to name a few—and I don’t spend as much time as professional pianists with the instrument. That will limit my skill somewhat, but I’m still quite competent and can play a lot of music I really love and care about.”

Simple conclusions stick. Those compressions of reality that we use to grasp complexities—they can become what we genuinely believe if we live with them for too long.

(I was a math and music person, wasn’t I?)

Try to avoid “can’t”s and “must”s. Try not to throw people into boxes too quickly. Less strong, short statements that preclude nuance. More acceptance of the bewilderingly broad scope of reality and possibility.

Cults // Communities

(Or: the downsides to acceptance.)

I was an Asian American math nerd and an atheist at a small, predominantly white Episcopalian all-boys school. I’ve been some sort of “outsider” for the vast majority of my life.

Many of my friends have, too. Some due to queerness, or neurodivergence, or intense care for things a lot of teenagers don’t or can’t value, or plain old-fashioned bullying.

When you’ve been an outsider for so long—watching other kids and book characters and people in those sappy teenage sitcoms make friends and feel belonging—you become very susceptible to the memes of the first community that accepts you.

My first was the competition math community.9

I appreciated that they were skinny, nerdy Asian kids. I appreciated that they got what it was like to grow up with intense pressure to succeed. (As a fifth-grader, I wrote in a letter to my twelfth-grade self, “I hope you go to Harvard or Yale”—insane behavior.) I appreciated that I could talk to them about math problems and chess and music. I didn’t know how to talk to my high school classmates, and they were a lifeline.

Over time, I learned this community’s values. They valued solving hard problems. They valued success. They valued collaboration. They valued improvement. They valued math above its baser cousins, science and economics, and far above the humanities. They valued “normal school” lightly. They valued people based on how well they did—“Olympiad qualifiers” garnered some respect; “MOPpers” garnered more; (people who didn’t do competition math didn’t exist on the scale.)

So I improved from “AIME qualifier” to “Olympiad high scorer” within two years. I aimed for 89.5s and no higher on report cards (they’d round up to A’s.) I talked about problems with all my math camp friends. I felt inferior around MOPpers and dismissed my classmates. To other memes I was more resistant: I loved music (and later, writing) too much to be convinced they were not valuable.

There are other communities, too. My friend Laura’s first was The Knowledge Society.

TKS valued—for some definitions of these words—impact, authenticity, self-promotion, emerging technology, fame, discomfort, and more. That TKS was the first is definitely a reason I tried so hard to fit in, she tells me.

I’d tried hard, too. I’d spent an entire year working my way through every past Olympiad problem that looked remotely approachable. I didn’t have a real tracking system, so I wrote up solutions in TeXeR, saved them, and emailed them to myself. (Even having lost my high school email, there are still two hundred of them in my personal inbox.) All this, with the primary goal of seeing math camp friends and other math people at MOP.

(In retrospect, what an insane decision to make. All that for a handful of people, who mostly existed online and in my head?)

Finally feeling accepted by a community does strange things to your mind. Not necessarily good or bad—just strange. You might want to fit yourself to them, to make sure they’ll never reject you. (Laura, seeking discomfort over and over again.) You might heedlessly absorb their values. (Was I supposed to care so little about high school?) It’s easy for them—their ideas, their people, their lenses—to take over your life.

Some communities are conscious. SPARC is many people’s first home. On the last day, the director teaches Why Everything We Teach You is Wrong, a class with (roughly) the premise of “because teaching is hard, we will imperfectly convey some ideas, you will interpret them wrong, and then misremember them even more wrongly.”

In a way, this is one of SPARC’s self-defense mechanisms. We don’t want to be crushed under the weight of our alumni’s expectations. Any community that is too comfortable, too welcoming is liable to its members feeling that it is the only place in which they will feel comfortable and welcomed. Some communities (cults) take advantage of this, but we don’t want to.

The world is too big and beautiful for your life to revolve around SPARC, or communities similar or adjacent to SPARC. (Or any one community.) You don’t always have to be an outsider. You don’t have to take that as a permanent label. When you’ve struck gold—when it shines so blindingly bright—when it overwhelms you with joy and giddiness and yes, this is my home now—that is when you are most vulnerable.

Seeing with clarity is so difficult when you finally feel seen, isn’t it?

Closing

Here is a list of people I wrote this for:

The 120+ campers I was a junior counselor to at five “rationality camps” these past two years: WARP, SPARC, ESPR ‘23; WARP, SPARC ‘24;

My younger sibling;

My parents;

Past versions of me (the ones that talked to students about this—he would’ve liked to have this all in writing);

Future versions of me (the ones that will talk to students about this—he’ll be glad to have this all in writing);

Anyone who can empathize with even one of these stories;

L and J, who inspired many of the thoughts here;

me.

You may or may not find any of this useful or true. No matter—what’s important is that some people do. (Those people may include future or past versions of you!)

Best of luck and lots of love.

[Thank you to Laura, Siva, and Ben for helping me edit this piece. Thanks to Magic: the Gathering for the inspiration on the section titles.]

I am not referring to physical self-defense; this likely cannot be taught through a blog post, and as far as I can see, the best physical self-defense is to get away very quickly.

Holding onto your own dreams and cares is one thing; learning what they are is the matter of a lifetime.

Though aligning yourself with other people or institutions is not necessarily good or bad!

When I refer to “rationality” in this post, I refer to LessWrong-esque rationality.

These are not bad memes, and in fact, are good for some people. They are simply powerful memes.

This is particularly important for “Verbalize // Vibe,” where I firmly believe that most people should do less sidestepping (but some people ought to do more sidestepping.) I think this is likely false for “Online // Outside.”

Please do not take this as “Andrew thought only ‘deep’ connections are worth making.” These were the kinds of connections I was missing at the time.

People sit in a circle, and one person is designated as the person in the “Hot Seat.” That person answers questions from everyone else for the next five minutes, then that person switches out of the Hot Seat for someone else. Play continues until everyone has been in the Hot Seat. Often, this game leads to very personal questions.

This was probably the best thing that’s ever happened to me.

In many ways I think self-defense is related to self-respect. If one respects oneself one will simply not be swept up by powerful memes. Alas, self-respect is difficult.

slightly late to the party but this is timeless enough. i think about these lessons that you taught me every day; thanks andrew <3